“Today let’s start a new decade, one in which we finally make peace with nature and secure a better future for all,” declared António Gutterres, the UN Secretary General, during the virtual opening event of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration in June. With environmental degradation already affecting almost half of humanity, and with every major scientific body declaring the next 10 years critical to confront the climate crises, the urgency to restore the health of our landscapes has never been greater. Having worked professionally as an ecological restoration planner in my home state of New Mexico for 13 years, I sat eagerly at the edge of my seat to learn from my global community of practice.

Para leer este artículo en Español, haz click AQUÍ

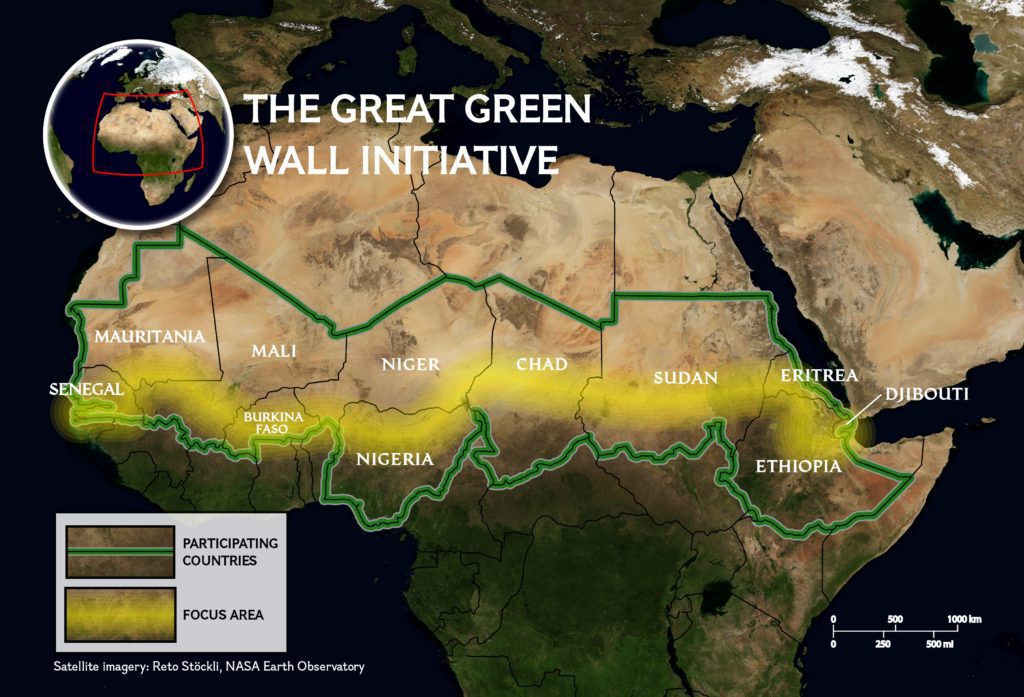

Map by John Kappler, National Geographic

We learned about restoration efforts around the world that involved massive community efforts, such as the million-tree initiative in Pakistan and the ambitious project called the Great Green Wall of Africa. Touted as the “largest human-made living ‘structure’ on earth,” this ecofriendly wall, we are told, will contain the sand dunes of the Sahara and support local livelihoods. Although containing the Sahara desert with any wall seems questionable, or that building another wall, even the green kind, seems like the last thing we humans need to do, at least there is a clear mandate that restoration has to collaborate with and support the local indigenous communities.

Several weeks after the UN event, Dr. Robin Kimmerer, the well-known Potawatomi restoration ecologist, gave a deeper perspective on this mandate to work with indigenous communities during the opening plenary talk of the 9th World Conference of the Society of Ecological Restoration: “This idea of mutual healing, of cultures and land, is the practice under the really big idea of how do we enact land justice. Justice for the more-than-human beings, justice for the people who are so often dispossessed from their homelands, to return people and their practices to the land as part of that sacred moral responsibility to care for the land.” The most challenging and crucial aspect of my own restoration work is reviving these cultural practices and relationships with the land.

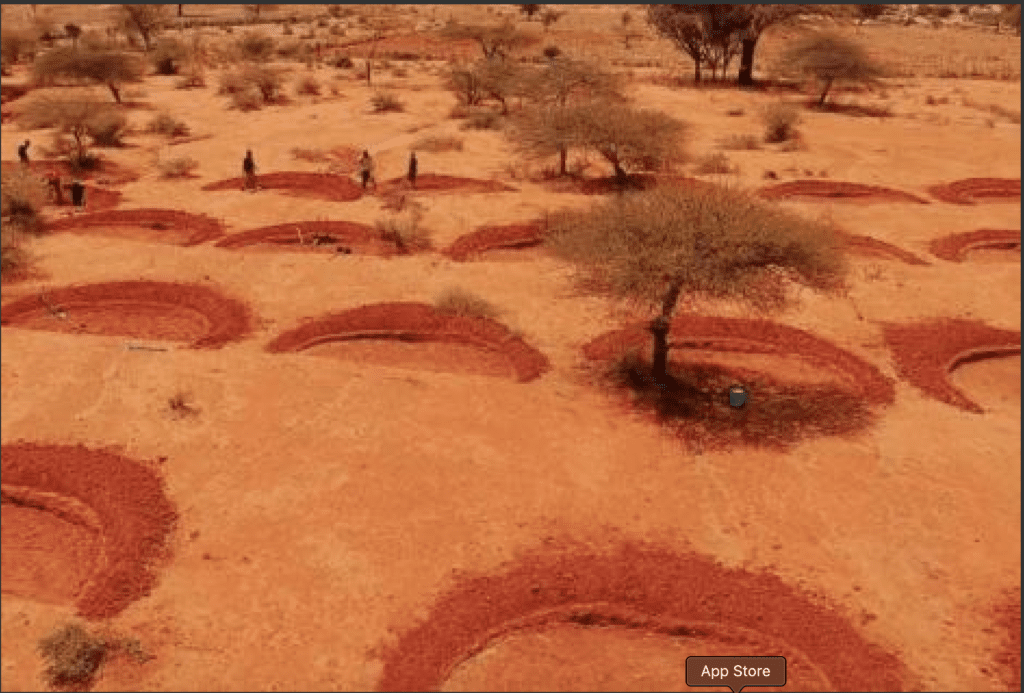

(Source: Kenyans.co.ke)

The mentioning of “culture”, however, was surprisingly absent from the televised UN event. This glaring omission became ridiculously blinding during the finale world premier music video by Ty Dolla and Don Diablo called “Too Much to Ask,” tailored to appeal to the #GenerationRestoration. None of what I am about to explain was provided to the viewer. The music video contained high-quality panoramic footage taken by drone showing hundreds of Maasai people in Kenya, spread out over hundreds of acres of barren red land, constructing half-moon shaped structures called bunds, about 15 feet long with shovels, hoes and lots of sweat.

Thanks to this earth-shaping community work, which saved water and fertile topsoil from being washed away after a storm, the barren land became covered with vegetation. Importantly, this community bund-making event is one of many old cultural practices across Africa to harvest rainwater, promote plant growth, and take care of the land. While there was hardly a peep about cultural practices on the land, it was all over the music video! There is a tendency to describe restoration work as a “new relationship” to nature, as based on a “very young’ science,” but actually, it is a very old human relationship to the land, a very old community-based science, albeit maybe a forgotten one.

Stimulated by the climate crises, examples of this old land-human relationship are popping up everywhere. Just beneath the cloud-piercing mountains surrounding Lima, Peru, about a hundred communities are removing 500 years worth of mud and rock that have filled in a network of stone ditches constructed during the Incan civilization and abandoned after the arrival of the Spanish. This network of ditches, known as amuna in Quechua, are designed to harvest and store rainwater underground so that water is available during dry periods. Just reviving 10 miles of the amuna, a small sample of the existing infrastructure, the nearby communities are already seeing more water flowing out of their domestic wells regardless of the changing climate. Since reviving these ancient cultural infrastructures, more crops are planted and more families are able to maintain good hygiene during the pandemic.

Along the northwest coast of North America, from Alaska to Washington State, various researchers, academics, and resource managers have teamed up with Canada’s First Nations communities to learn how to sustainably grow clams using an old ocean gardening technique. These clam gardens, which First Nation communities have been building and managing for longer than five thousand years, involves constructing rock terraces along the shoreline when the ocean is at low tide. Not surprisingly, a slew of scientific studies have proven the efficacy of clam garden work, with one study showing the growth of several clam species improved by 151% to 300%. In a time of plummeting fisheries and shellfish production worldwide, these clam gardens stand out as a shining star, shedding light on the importance of knowing history and culture when it comes to cultivating food from the ocean. Another amazing example of cultivating food along the edge of the ocean comes from Hawaii, where applying old indigenous land management practices at the He‘eia National Estuarine Research Reserve has recently shown to not only increase food for both people and animals, but has also brought back endangered shorebirds that even the eldest of elders have never seen before.

Then there is the example of Indigenous fire, which has rightfully received lots of press lately. Indigenous fire, sometimes called cultural fire, is one of the oldest land management practices common to almost every ethnic group on every continent. Yet only when faced with the threat of megafires these last couple of years do forest-managing agencies finally want to listen and learn from Indigenous people. Every forest on earth vulnerable to catastrophic fire can trace its start date to when colonization dispossessed the original peoples from the land.

“We are fortunate here,” says Marianne Ignace, who has been reviving cultural fire practices on their traditional territory of the Secwepemc Nation in British Columbia, “that some of that [cultural fire] knowledge still exists in the older generations although it has been undermined and outlawed for over a hundred years.” These cultural fires have brought back important plants not seen since Indigenous culture was outlawed. All this is taking place not far from where the remains of 215 children were recently found buried next to the old Kamloops Indian Residential School. The horrors and pain of genocide, and the beauty and resilience of culture, remind us how connected it all is: restoring justice, healing, and the land.

Another example comes from my home state of New Mexico. As hotter temperatures melt the mountain snow much earlier than before, the nourishing waters are passing by the farmlands before the farmer has even planted. Consequently, federal land agencies are in discussions right now with local farming organizations to build micro-dams or mini-reservoirs in order to capture this water in the mountains for when the farming is ready. It turns out, this same idea and concept was practiced by New Mexico’s Pueblo communities for millennia. They built water-harvesting structures and ancient gardens out of local rock and earth almost everywhere water could be collected, “inviting the rain to stay,” as one scholar put it. Through people power, the Pueblo communities created wetlands in the desert, and even grew water-loving crops like cotton in places that today’s experts emphatically say would be impossible.

Another example comes from my home state of New Mexico. As hotter temperatures melt the mountain snow much earlier than before, the nourishing waters are passing by the farmlands before the farmer has even planted. Consequently, federal land agencies are in discussions right now with local farming organizations to build micro-dams or mini-reservoirs in order to capture this water in the mountains for when the farming is ready.

It turns out, this same idea and concept was practiced by New Mexico’s Pueblo communities for millennia. They built water-harvesting structures and ancient gardens out of local rock and earth almost everywhere water could be collected, “inviting the rain to stay,” as one scholar put it. Through people power, the Pueblo communities created wetlands in the desert, and even grew water-loving crops like cotton in places that today’s experts emphatically say would be impossible.

The global call to heal the Earth’s wounds is a powerful moment of cultural recognition for everyone. As Dr. Kimmerer explained, every person is indigenous to some place, and every place is the homeland to someone. Especially for indigenous communities across the continents of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, whom for generations have been denied their rightful place at the table of humanity, it is a time of reconciliation and of pride, where their cultural practices are recognized as a means to heal a wounded Earth and a wounded people. As the young poet, Jordan Sanchez, said during the UN conference:

“Resilience, we stand on our own two feet. I’ll tell you, reimagining the future has never tasted so sweet…The promise of restoration lives within us.”

It does indeed.

A different version of this article appears in Resilience.org.

Maceo Carrillo Marilet, PhD, Taino/Mexican is an ecologist and educator, who works on various environmental restoration, water conservation, and community-based education projects. He is Assistant Professor in the Community and Regional Planning Department, at the University of New Mexico New Mexico, and can be reached at [email protected]

amunas bunds clam garden ecological restoration indigenous fire